Brazil’s Military Dictatorship: Bolsonaro’s Godfather Is Home from Haiti to Roost

By Dady Chery

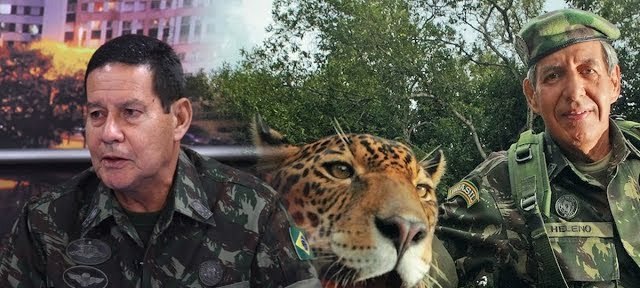

Haiti CheryIt is bittersweet to be right about my prediction that the occupation of Haiti by Brazil would destroy its democracy. The real power behind the far-right congressman and former army captain, Jair Bolsonaro, who will take office on January 1, 2019 as Brazil’s president, is his mentor, the retired General Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira. Mr. Ribeiro Pereira will likely become the most powerful man in Brazil and the next minister of defense. He was the first commander, in 2004 to 2005, of the infamous United Nations Mission for the (de)Stabilization of Haiti (MINUSTAH).

It is important to note that MINUSTAH’s architect was not the Brazilian right, but Celso Amorim, when he was the foreign affairs minister in President Lula da Silva’s leftist government, together with Bill Clinton. Lula has been convicted of corruption and is now in prison. Nevertheless, if the Brazilian left had won the October 2018 elections, the next minister of defense would probably have been Amorim. Mr. Amorim’s last stint in Haiti was as the leader of an Organization of American States (OAS) observation mission for the fraudulent 2015 elections. Nothing whatever would have changed with regard to the countries that Brazilian troops currently occupy mainly for the United States, France, and Canada. There are nine such countries now. Venezuela might be the next.

In his capacity as MINUSTAH commander, Ribeiro Pereira is associated with a notorious massacre on July 6, 2005 in the Port-au-Prince slum neighborhood of Cite Soleil, after which he quickly returned to Brazil. He has been suggesting ever since that he had behaved with restraint while under pressure to use excessive force. Statements from MINUSTAH to the public about the massacre have disagreed with its after-action report to the US Embassy. In that report, MINUSTAH described a firefight that “lasted over seven hours during which time their forces expended over 22,000 rounds of ammunition,” and an operation that involved 1,440 troops: 1,000 who “secured the perimeter” and 440 who engaged in a raid. It has been suggested that Ribeiro Pereira left Haiti for fear of “being hauled before an international court for war crimes.”

One may evoke sophisticated geopolitical reasons why the Brazilian government would occupy a friendly country far from its borders, but I believe the reasons for the supposed humanitarian intervention in Haiti were rather mundane. The one most often cited is Brazil’s ambition to enhance its image on the world scene since the United Kingdom and Soviet Union blocked its permanent membership in the UN Security Council in 1945 because of its military and financial weakness. Indeed, on his accession to MINUSTAH, Ribeiro Pereira said, “this is an occasion to project the name of the country.” Likewise, when Dilma Rousseff became president in 2011, she named Celso Amorim her minister of defense and credited him with “an independent foreign policy that put Brazil at the same level as the leading nations of the world.”

Another reason was the use of Haiti as a testing ground for military hardware, such as armored amphibian vehicles manufactured in Brazil that could then be sold as being battle-tested. This was important for the Brazilian army brass, which considered Haiti to be perfect for this project because the population was unaware that it was at war and posed no risk.

For the Lula and Dilma administrations, Haiti probably also satisfied a need to scatter their most racist and fascist elements to other countries for their soldier games. Before MINUSTAH, Ribeiro Pereira was a military attaché in France from 1996 to 1998. It is unclear what he did in that capacity. After MINUSTAH, he was army commander in Amazonia, but Lula was forced to remove him from this post after he publicly criticized the president for having a “regrettable, not to say chaotic” Indian policy because he had granted government land to several communities in the area. Ribeiro Pereira’s final job before retirement was in the Department of Science and Technology. He referred to that position as “being placed in the professional refrigerator” and turned by Lula into a “stereotype of the wrong man in the wrong place.”

After his retirement, Gen. Ribeiro Pereira, who began his military career during Brazil’s last dictatorship, became an unofficial spokesman for MINUSTAH as well as the Brazilian Army. Year after year, he advocated for the renewal of MINUSTAH mandates. In 2011, when Defense Minister Celso Amorim began to plan a withdrawal of Brazil from MINUSTAH, Ribeiro Pereira pointedly warned him not to give the army a “leftist ideological imprint,” and Amorim promptly dropped the project. In the run-up to Brazil’s 2018 presidential elections, Ribeiro Pereira publicly defended the 1964 coup against what he calls “the country’s communization.” He also began to advocate for a Haiti-style pacification regime for Brazil’s favelas, complete with immunity for the military, collective search-and-seizure warrants, and even the use of snipers to kill presumed criminals.

Ribeiro Pereira speaks casually about his work to structure the future management of Brazil’s government. He is described as having a father-son relationship with President-Elect Bolsonaro. Another of his protégés is the Vice President-Elect, the retired Gen. Hamilton Mourao, whose father was a coup general. Mourao has not only publicly defended the 1964 coup but also criticized Brazilians as being afflicted with a legacy of the “indolence of the Indians and sly spirit of the Africans.” Men like Mourao are probably representative of those who were charged for over 13 years by the United Nations with promoting democracy in the world’s first Black Republic.

The military managed to win Brazil by the ballot because it hijacked as its main issue the rampant government corruption that had been exposed by well meaning people like Judge Sergio Moro. But if the military had lost the elections, it would probably have staged a coup, and the threats were there. Many leftist Brazilians are angry with the Workers Party’s last-ditch attempt to hold on to power. They fail to see that their made-in-Haiti military dictatorship had become inevitable, and their military men had become impatient with legal procedures precisely because the army had already grown too strong. Thanks in large part to the United Nations and Gen. Ribeiro Pereira, the security apparatus that grew out of sight has ballooned beyond control. In Haiti alone, over 37,000 personnel were trained and recycled back into Brazil. Among them were the first soldiers of the Unidades de Policia Pacificadora (UPP) of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, trained in urban warfare in Port-au-Prince’s slums. Sadly, the sun has set on Brazil’s democracy, and the snipers and their masters are home to roost.

UPDATE #1. November 13, 2018. Bolsonaro named Gen. Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira as the Director of the Presidential Office for National Security and appointed as Brazil’s Minister of Defense retired army Gen. Fernando Azevedo e Silva, who was MINUSTAH’s operations chief under Heleno’s command.

UPDATE #2. April 2, 2019. The more complete made-in-Haiti-team of Brazil’s latest junta is as follows: Gen. Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira, Director of the Presidential Office for National Security; Gen. Floriano Peixoto, Chief Minister of the General Secretariat of the Presidency; Gen. Fernando Azevedo e Silva, Minister of Defense; Gen. Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz, Secretary of the Government; Capt. Tarcisio Gomes de Freitas, Minister of Infrastructure; Col. José Arnon dos Santos Guerra & Col. Freibergue Rubem no Nascimento, Ministry of Justice; Gen. Edson Leal Pujol, Army Commander; Gen. Otávio Santana do Rêgo Barros, Spokesperson for the Presidency of the Republic; and Gen. Ajax Porto Pinheiro, Special Adviser to the Supreme Court President.

Sources: Dady Chery is the author of We Have Dared to Be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation. | This article is also available in Portuguese.

Comments

Brazil’s Military Dictatorship: Bolsonaro’s Godfather Is Home from Haiti to Roost — No Comments