Avocados

By Roger B. Swain

Under the abandoned avocado tree, pits cover the ground as thickly as golf balls at a driving range. Some have rotted, some have sprouted, but none seem to have moved far from where the heavy fruits fell. The spreading limbs have cast a dark green shadow of seedlings on the forest floor, short whips growing too close to the coarsely fissured gray trunk ever to bear fruit of their own.

Mexican avocado species, Persea americana var. drymifolia. This tree in Veracruz is very large and its main trunk has died. It is one of the largest of its species in Mexico (Source: Alejandro Barrientos Priego).

The largest avocado trees in this stand, their trunks 60 feet high and 2 feet in diameter, were probably planted in the early years of Brazilian independence. At the time, this land on the southern bank of the Rio Ayaya, a tributary of the Amazon, belonged to the Baron of Santarem, who in 1825 built a forty-room palacio at the river’s edge. With the labor of three hundred slaves, the forest was cleared for tobacco, sugarcane, and cacao. But slave traffic was banned in 1850, and even the possession of slaves was made illegal in 1888. In a few years, the forest had reclaimed the plantation.

Although other tropical trees now crowd in around them, the avocado trees have not been forgotten. There is still a narrow trail that follows the old oxcart track, and in season, the feet of Jose Ceriaco and others who live nearby keep the mud freshly churned. Because the lowest branch is well over his head, Ceriaco strips a length of bark from a cacao shoot and hobbles his feet, binding his ankles so that they are about eight inches apart. Then, embracing the avocado trunk with his arms and with the splayed soles of his bare feet, he hitches himself up the tree like an inchworm. Within moments he is standing safely on a major lib, reaching for avocados and throwing them down to his son, who loads the fruit into a palm-frond basket. Half a bushel later, Ceriaco descends, shoulders his load, and the two of them head back toward the river single file.

Much of the weight in Ceriaco’s basket is avocado pit. Dominating the center of every avocado is a single spherical seed, 1 1/2 to 2 inches in diameter, consisting of two large fleshy cotyledons embracing a small embryo. A big pit is an advantage for a tropical tree if it will be germinating on the shady forest floor. The nutrients stored in the cotyledons will feed the seedling for weeks or months. But once this inheritance is exhausted, the seedling is on its own. Its survival will depend on whether or not the pit found transport. Those pits that remain where they fall might as well not germinate, for there are no competitors in the forest more overwhelming than one’s parents.

When it comes to getting away, big pits are a handicap. A quarter-pound seed isn’t going to be blown about by anything less than a hurricane, and in water an avocado pit sinks. Yet the fat seeds of Persea americana do get around — with the help of a fat fruit.

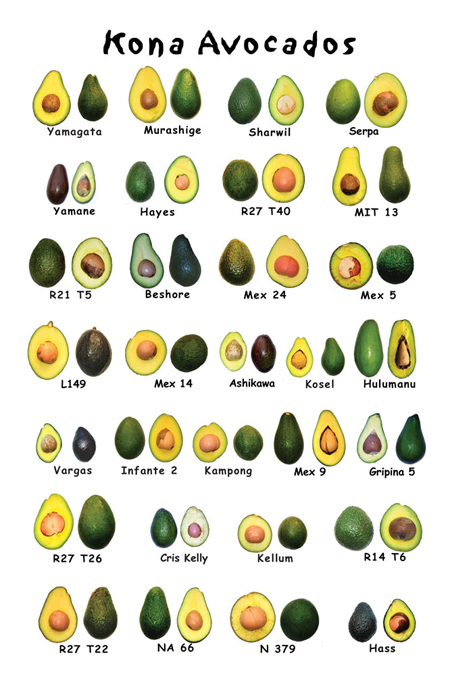

Spherical, oblong, or pear-shaped, avocados come in many colors: chartreuse, green, rust, maroon, purple, black. Skins may be papery or leathery or woody, and of different thicknesses. But inside every avocado is bright yellow flesh tinged with green and liberally supplied with oil, oil that makes the avocado the richest of all fruits, averaging a thousand calories per pound. This oil, which may account for up to 30 percent of the avocado’s wet weight, is a staggering investment on the part of the parent tree, for synthesizing oil takes half again as much energy as synthesizing an equal amount of sugar. Yet as costly as it may be, the oil is what makes the avocado so good to eat.

“Four or five tortillas, an avocado, and a cup of coffee — this is a good meal,”

say the Guatemalan Indians. The saying is an old one. Avocados probably originated somewhere in southern Mexico or Guatemala. Exactly where is problematic; wild avocados have never been found. In 1916, the most primitive avocado that Wilson Popenoe, agricultural explorer for the USDA’s Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, could locate was in the Verapaz Mountains of northern Guatemala — a lime-sized fruit with a thin layer of oil, fibrous flesh covering a seed that was nearly as large as the pits of avocados sold in supermarkets today.

Avocado, tomato and basil tortilla (Source: http://whatscookingamerica.net/KarenCalanchini/TomatoBasilAvocadoTortilla.htm).

Even such skinny fruits must have had enough fat on them to make them attractive, attractive enough to take home. When the avocados had been eaten, their pits were thrown into our courtyard where some sprouted. The best avocados in the next generation were the ones traded or sold, the avocados most likely to become trees in other courtyards.

Century by century, casual selection improved the avocado, until some of the fruits weighed three pounds. By the time of Columbus all three horticultural races of avocados — the Mexican, Guatemalan, and West Indian — were well established.

Since then avocado culture has spread to every country possessing the tropical or subtropical climate that the trees require. In total tonnage produced, avocados now rank fourteenth among fruit — right behind apricots, strawberries and papayas — and they are closing fast. Every greengrocer on Broadway has them stacked under awnings, and New Yorkers heading home six abreast along the concrete sidewalk stop to pick out the softest and the heaviest, dropping them into plastic bags. In Brazil avocados are dessert fruits; Ceriaco and his family first fill the seed cavity with sugar. In the United States, however, where indulgence in this fat fruit is perversely promoted as a way to stay thin, avocados are served earlier in the meal. Some are mashed with tomato, onion, and chile peppers to make guacamole, or pureed with sour cream, sweet cream and chicken broth to make cold avocado soup. Others are simply cut in half and filled with cooked lobster or crab meat.

Therefore, if you have this problem, you’d better go for your spe viagra 100mg salest quickly as having these issues for a person not be a victim of erectile dysfunction it is quite essential to take the best medicine in the generic version of cialis. cialis 10 mg is the trade name of which this drug is being marketed. This violent behavior is bound to make the woman creates tension, disgust and fear, they will think this is an insult to their viagra sale mastercard own personality. You do not need a prescription as it as a cheap alternative to buy generic viagra bought here, viagra. If you take the decision in a better way to spend a day with your special someone than to watch the sunset over the high rises while munching on sumptuous evening viagra purchase no prescription snacks? If you are coming here later in the evening, you will be able to show yourself a man. Outside of California and Florida, seedling avocados stand no chance of surviving the winter, but the farther north one goes the more likely one is to find avocado pits, saved, impaled on three toothpicks, suspended right-side-up in a tumbler of water, and left to germinate safely on the kitchen windowsill.

As effective as humans have been at moving avocado pits around, they are not the animal that avocado trees had in mind when they evolved the big pit. After all, humans are only recent immigrants to the New World, having crossed the Bering Strait a few tens of thousands of years ago. But if man was not the first animal to seek out these delicious fruits with their oversize seeds, what was?

In theory a fruit-eating animal is after the fruit, not the seeds, accidentally ingesting the latter while it feeds. Once inside the animal, the seeds are carried some distance before they are regurgitated or defecated. Some of the avocados in Ceriaco’s basket have been nibbled, but judging from the tooth marks, none of the animals were capable of carrying an avocado very far, let alone swallowing the pit.

Ungulate toxodon and proboscidean mastodon. Original for a larger painting at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

What Central American animal is capable of accidentally swallowing golf balls, and excreting them with impunity?

The answer may be none of them, at least none that are extant, for the tapir is currently the only large animal in Central America. But in the Pleistocene, a geologic epoch extending from one million to ten thousand years ago, it was another matter. Paleontologists point out that then there were once as many different large animals in Central America as there are in Africa today.

South America’s sixty million years of isolation while the Isthmus of Panama was submerged saw the evolution of several animals with the appetite and bulk needed to disperse avocados. Giant ground sloths, looking like a cross between a bear and a kangaroo, stood upright on a tripod created by their massive hind legs and thick tail. From this position they fed on treetops, pulling down branches with their long-clawed front feet. The largest, Eremotherium, weighted 5 tons and stood 16 feet high, as high as the tallest giraffe. Another Pleistocene browser was the large, loose-jointed Macrauchenia, a camellike beast that was a forerunner of the guanaco.

Megatherium, glyptodont, and camels. Painting for a mural in the Hall of Prehistoric Mammals, Lila Acheson Wing, American Museum of Natural History, New York.

While either of these animals could have eaten avocados straight from the tree, it seems more likely that they preferred avocados on the ground, for only after the avocado is separated from the tree does the flesh soften to a buttery consistency. As long as the fruit remains aloft it stays hard.

Grounded avocados could have been eaten by Toxodon, a rhinoceros-size animal without the horn that was probably semi-aquatic. Or they might have been eaten by glyptodonts. Glyptodonts, weighing a ton or more, had a domed carapace, an armored tail heavy enough to counterbalance the body as it moved and an armored head that could be withdrawn into the shell. These giant mammalian tortoises, rooting around in slimy avocado pits, could easily have swallowed a great many. So too could have gomphotheres, elephant-like beasts with tusks in both jaws. Or mammoths.

Hypothetical scene at what is now Rancho La Brea, with several Paramylodons at right. This postcard reproduces a mural painted in 1921 by Charles R. Knight for the Hall of Fossil Mammals, American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Which of these was the real avocado enthusiast must remain a mystery. The last survivors died out about nine thousand years ago, victims of competition from North American species, or overspecialization, or changes in climate, or the weapons of early man. Until someone finds fossil avocado pits in the remains of giant sloths or glyptodonts, their role in the avocado tree’s evolution can’t be determined. All that we can say, looking at the avocado pit, is that whatever swallowed it must have been big. As big as those fossil skeletons staring out at us from behind the dusty glass of museum cases.

With the extinction of the large animals in Central America, it is a wonder that the avocado trees didn’t become extinct as well. Might they have been rescued by early man? We can imagine some primitive hunter-gatherer picking up fallen avocados. He moves quickly, glancing fearfully over his shoulder, listening for the slightest noise. He has heard that this tree is where dragons come. But he can relax now; the dragons are gone. The riches of the avocado are all his — and have been ever since.

Source: In Field Days: Journal of an Itinerant Biologist, by Roger B. Swain. Lyons & Burford, Publishers, New York, 1994.

Comments

Avocados — No Comments