Interview: Haitian-Born Author Dady Chery Dissects Haiti’s Ongoing Occupation

Gilbert Mercier

Haiti Chery

Dady Chery was born and raised in Haiti and, as such, is proud to call herself “natif natal.” Before the 2010 earthquake, her professional life was wholly dedicated to science. Like so many Haitians, either still living on the island or from the diaspora, the quake turned her life upside down. Her book, We Have Dared to Be Free, was written between 2010 and 2015. It is based on a lifelong wealth of knowledge, and it is essential to understand Haiti’s complex and extraordinary journey.

Dady Chery. Thank you. I began to write this book the first weekend after the January 12, 2010 earthquake, really as part of my journal. Until then I had been writing my observations mostly about the natural world, but as I went through the uncertainty of not knowing whether my family in the capital city of Port-au-Prince had survived the disaster, my focus completely changed. I became compelled to write about myself and my family as a sort of record keeping. This grew very quickly into observations and analyses about Haiti, as it became apparent to me that there was a tremendous contrast between what was being presented to people by the international press and what was really going on in Haiti. For example, in the Haitian French and Kreyol-language press, there were countless stories about Haitians who saved each other during the first 36 hours after the earthquake, but in the English-language press, Haitians were presented as being completely desolate, paralyzed, and helpless.

Of course, the stage was being set for a major infusion of aid money, but I could not have figured this out then. When Clinton moved in with his rich friends and tried to take over the governance of the country in spring 2010, I was as surprised as everyone else. But I decided to make notes on all of the goings on and tease out the most important elements. When the cholera came, because of my background as a professor of microbiology, I was immediately able to figure out that it had been introduced by a foreign source, and I was the first one to write this. I knew what was possible and what was not, even when Western scientists and journalists were trying to confuse the issue about the involvement of the UN. But this book is much more than this. As you say, it has been a five-year journey.

In the end, this book is not only my record keeping and analyses of the last five years about Haiti, but also a love letter to my country of birth. It is the kind of book that I would want to read. I titled it We Have Dared to Be Free, because in the final analysis, after I put all my thoughts together, the core of the book is people’s struggle for freedom, not only in Haiti but everywhere. “We have dared to be free” is a phrase that I borrowed from Jean-Jacques Dessalines’ eloquent 1804 Declaration of Independence, in which he compares our liberation as the first black republic to the first steps of a child who transforms his weight from being an impediment to becoming an instrument with the momentum to break the boundaries of space.

I hope that people who really want the truth about what has gone on in Haiti during the last five years will pick up this book, read it, discuss it in book groups and other settings, and pass it on. I hope the book will help to expose the fake humanitarians for being the predators that they really are. But more than anything, I hope that it will arm people with tools to dissect what is really going on and wrench Haiti and other places from the neocolonial onslaught.

GM. Your book was written in the past five years but it encompasses more than two centuries of Haiti’s rich history.

DC. It is not possible to talk about Haiti without talking about Haitian history. History is not an abstraction for us. Our revolution is not a yearly occasion to get drunk and blow firecrackers for a day. Our history is alive. Our revolution is in progress. When we encounter new political situations, we naturally think of them in the context of our history, and this is absolutely correct, because everything going on in Haiti right now goes back to the fact that we did what was probably the most audacious thing in human history. As a group of slaves, we took, by force, an incredibly valuable piece of real estate from our supposed masters, because we had been kidnapped to that land and mixed with it our sweat and blood, and all our miseries and desires. We are Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s Le Petit Prince; the volcano is ours because we swept it every day.

It is almost impossible right now to popularize and trivialize Haitian history, and I’ll tell you why. This is like the difference between decorating a corner of a former cow pasture with a few cow sculptures, versus dealing with the pasture while there are real animals marching around, making noise, dropping cow pads, and chewing on the grass. History in real time is incredibly messy. The fact is that Haitian history is world history. Our slave revolution transformed world ideas of the rights of men and forced Europeans and Americans to begin to walk the talk of their revolutions. We changed the maps or North and South America. In fact, we changed world history in ways that most people do not realize. The major reason why Russia beat Napoleon at Waterloo, for example, is because Russian generals had borrowed from Toussaint’s playbook the strategy of retreating and burning everything to deny provisions to the enemy.

GM. Haitians are incredibly proud. Can you tell us why?

DC. Well, most Haitians would tell you that it’s because we’re all beautiful and smart. But seriously though: we are self-emancipated, self-defined black people, and we know our history. We know that we can beat the French, British, Spanish, and other supposed invincible powers, because we have done it. Nobody can tell us that we’re not good enough for anything, because we know that we can compete at the world-class level at anything. We beat Napoleon when he was at his peak. Our contributions of statesmen, scholars, and literary lights to the world are numerous and are absolutely first rate by any standard.

GM. What can other people learn from Haitians?

DC. They can learn their future from Haitians. Let me explain. In the last 30 years or so, and especially in the last 10 years, Haiti has become a laboratory in which the world’s most reactionary forces and institutions have experimented with methods of oppression. In effect, a coalition of colonial powers like the US and France; want-to-be colonial powers like Canada, Brazil, South Korea, etc.; and other entities like the USAID, UN, NGOs, World Bank, IMF, and IDB have latched on to Haiti. They have done this, not only to exploit Haiti itself, but also to learn what works in Haiti so that they can take home the more successful methods. There are lessons in Haiti for everyone. We are, of course, resisting the imperialist onslaught. It is to the world’s advantage to help us in our resistance, because we can also learn and export methods of resistance. I completely believe that if most of the world’s people could look in a crystal ball at Haiti’s future, they would see their future too.

GM. How do you plan to keep fighting what you called the “peddlers of despair?”

DC. More than anything, I want to continue to inform people about the truth of things. About their own power. Those who work to demoralize people are fundamentally cowards. They have to believe that every action issues from power, and this is the view that they present to the world, mainly because they are unwilling to take the chance to act. The Haitian Revolution, the US labor movement, and countless leaps from the human imagination happened because people at the absolute bottom of society dared to believe that together they could exert real power. They were willing to put their lives on the line to change their situations. The next 20 years or so will be a serious test for humanity, because the pressures of climate change will generate a lot of displacement, homelessness and hunger. The rich will not be able to solve the world’s problems. What it will take to effect real change will be a quantum leap in human moral evolution. I hope to be part of that change.

GM. Parts of your book read like a manifesto. Do you have any political ambitions?

DC. Haiti is under foreign occupation. I have no desire at all to be an occupation candidate for anything. None. Zero. There are many ways to contribute to change in the world. There is room in Haiti for a new Toussaint, Dessalines, or Dumarsais Estime, and many others; or the Haitian versions of Mohandas Gandhi, Jose Marti and Camilo Cienfuegos, and Che, and Fidel. Revolutions are cooperative affairs. It takes all sorts. Right now, I’d rather be a spotlight on or a clog in the machine.

GM. What is next on your plate?

DC. My next project will probably be about climate change.

GM. Thank you Dady Chery.

DC. Thank you, Gilbert.

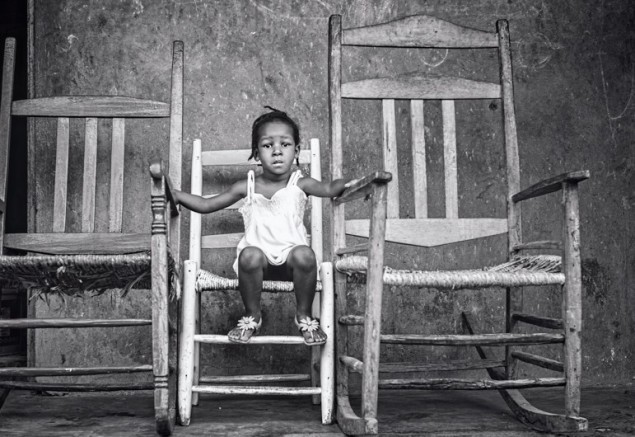

Sources: News Junkie Post | Photographs one, three, five, six, and ten by Alex Proimos; Photographs two, eight and twelve from Blue Skyz Studios archive; photographs nine and eleven from United Nations Photo archive; photograph seven from Ansel archive.