Food for the Gods: Link of Vodou to Haiti’s Agriculture, a Legacy of the Ancestors

By Dady Chery

Haiti Chery

Haitian religion and culture are so linked to local agriculture that Vodou ceremonies are routinely called manje lwa: food for the gods. Our lwa (gods, spirits, deities) must be fed. They are not eternal and can only exist so long as they continue to be summoned to participate in human affairs. In other words, their strength comes from ritual remembrance celebrations. During these feasts, the gods and their communities partake of local foods. The gods become empowered in direct proportion to the quantities and varieties of favorite foods that are offered to them, and the care that is put into their preparation and presentation.

The spirits of Vodou are, for the most part, venerable ancestors. They are not worshipped but respected, loved, and sought after, mostly for advice, protection and blessings. To summon them requires certain formalities. One does not greet an important ancestor without at least cooking a chicken and throwing a party, not for him or her alone, but the entire neighborhood. The practices of Haitian Vodou represent religion, unadulterated, unappropriated and at its best: not an infantilizing force that habituates people to their prostration before a greater power, but a cultural force that anchors people in the lands and waters around them and furnishes them with the practices for a joyful, sustainable life.

Vegetables aplenty

Westerners are so fascinated with the blood offered to Vodou gods, that many imagine the gods eat nothing but animals. I will not address here the hypocrisy of people who care nothing about how the beasts they eat have spent their lives, how they are slaughtered, whether they are thanked for their flesh, or if half of it winds up in a garbage receptacle. Instead I will first discuss the vegetarian foods routinely eaten by the Haitian lwa. Local fruits, vegetables, and the plants that produce them are essential to Vodou service in every respect. Plantains, rice and yuca among many others, are consumed by Vodou’s most venerable deities. Even Papa Legba, who guards the gateway between the spiritual and material worlds, needs these foods. He is the first spirit always to be called in any ceremony: the one who gives humans access to all the other spirits. If Legba is not empowered, no Vodou service can happen.

The tree of life – The gods of ancestral wisdom and knowledge, Danmbala Wèdo and his wife Ayida Wèdo, who are traditionally represented as a pair of serpents, favor the banana/plantain tree. In Vodou mythology, the banana is the tree of the first and greatest Vodou priest and priestess, and the serpent is thought to have fed on the fruit. The tree symbolizes eternal life because it is hermaphroditic and can grow continually from new shoots. The huge leaves are a conduit to Ginen: the Haitian slaves’ earthly paradise. In some ceremonies, such as the consecrations of drums or foods, the floor of the Vodou temple is covered with banana leaves, and symbolic actions are performed on them to represent the voyage of the objects or foods to Ginen for blessings. Interestingly, plantains were a major food for the slaves in colonial times; bananas and plantains are thought to have been the earliest fruit crops, originating in New Guinea around 8000 BC and reaching Africa by 3000 BC.

Rice and beans – The great spirits Danmbala and Ayida Wèdo look favorably, not only on plantains, but also on offerings of rice, milk, eggs, and white pastries. Èzili Freda, goddess of love, beauty and art, is one of several other deities who enjoy white foods. She is fond of rice pudding, and she also likes sugar-sprinkled fried bananas, mangoes with white flesh, fried eggs, and milk flavored with cinnamon. Other deities who favor these foods include the water spirits, such as Lasirèn, the goddess of the ocean and music, and Agwe, the god of fishing and sailing. The Ogou family of gods, who preside over war, metallurgy, fire and lightning, are not particular to white foods, although they too eat rice; they take their rice cooked with red beans. In every case, the varieties of rice and beans favored by the gods are local.

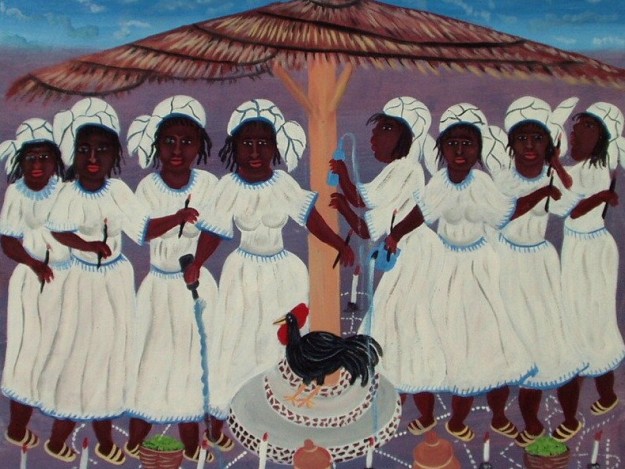

Corn and yuca – At Vodou services, corn is never far. For example, the sacred drawings, called veve, are usually made with corn flour. The priest or priestess sprinkles the flour in the appropriate pattern(s) for the god(s) being summoned, on the ground of the Vodou temple, which is a covered circular courtyard with a central post. The ritual offerings of foods are ultimately put on these drawings, which are thought to focus the energies to call forth the deities. Corn, grilled on the cob, is also a staple of Vodou celebrations, together with cassava and grilled peanuts. Such foods are typically arranged in small clusters on the veve, and they are often sprinked on ceremonial animals. Akasan, a corn-flour drink, is also often served at services.

Yuca (yanm in Haitian kreyòl, and the root from which cassava is made) is so important that it is central to a two-day harvest festival. This Vodou festival of thanksgiving, called Manje Yanm, happens around November 25-26. Manje Yanm commemorates the connection made by yuca between Africa, where it originated, and the New World; it also celebrates the Vodou god of agriculture, Zaka, usually affectionately called Kouzen Zaka (Cousin Zaka). On the first day of the festival, fresh yuca and other foods are harvested, consecrated, and offered to Zaka overnight. On the second day, the foods are cooked, the portion for Zaka is buried, and the rest is eaten in a feast that usually includes, in addition to yuca, plantains, rice and beans, avocado, corn, barley, and fish. Only then, with Zaka’s blessings, can the harvest continue.

Animals

The great majority of the Vodou gods eat meats, although Kouzen Zaka mostly favors the fruits of the land, and Gran Bwa, the god of the forest and of herbal medicine, is partial to peanut cakes, bread, and cornmeal, and he appears to be vegan. Offerings of animals are quite dear for most Haitians. Furthermore, with regard to animal offerings, the gods are extremely particular. In every case, as part of the ceremony of sacrifice, the animals are offered food before their slaughter, and they are considered to become one with the person who called for the ceremony at the instant they accept this food. Moreover, at that moment, their life’s energy is accepted by the god being summoned, and so such animals are treated with great respect.

The animals to feed the gods include doves, chickens, roosters, pigs, goats, oxen, bulls, and fish. Everything is specified: from the age of the animal, its color and patterns, its treatment before it is killed, the prayers that precede the slaughter, the slaughter itself (including the consecration of the instrument used to kill the animal, and rapid and ritualized method of killing), the offering of the animal’s blood, entrails and uneaten parts to the god, to the final presentation of the meat as a cooked food. Consider for example, the case of Papa Legba. His vegetables must all be grilled on an open fire; his sacrificial animal, usually a rooster, must be killed and quartered without breaking any of its bones, prepared without removing its feet, except for the nails and spurs; and finally, all his foods must be served in a red calabash.

Among the gods who like white foods, Agwe will accept white hens, white sheep, or white goats. On the other hand, Danmbala and Ayida Wèdo, who are snake gods, will not take sheep and goats but will accept white chickens; Èzili Freda prefers white doves. The Gede family of gods, who rule over death and sexuality favor black foods, including black chickens, black roosters, black goats, black cows, or salted herring, depending on the god. Bosou, the god of virility (of men and seeds) and violence, likes black pigs, as does Èzili Dantò, the goddess of fierce love and motherhood.

Black pigs also feature in the Manje Mò, a ritual feeding of the ancestors that takes place around the end of April. Typically, a stew is prepared, entirely by men and without salt, that contains corn, red beans, beef, and pigs’ feet. It is served to the dead, along with melons, grilled peanuts and corn on the cob, coconut, milk, rice, white cakes, soda and rum, in a room that is shut for several hours while prayers and appeals are said outside. Finally the head of the family knocks on the door and then enters; he returns with the foods, which are first offered to the four points of the compass and then the children, and the rest of the household. A portion is also put at a crossroad for Papa Legba.

Drinks and gifts

Kleren (a Haitian partially distilled rhum), refined rhum, coffee, and carbonated sweet cola, all manufactured in Haiti, are the gods’ favorite drinks; tobacco, cigars, cigarettes, flowers, and locally made perfumes are among their favorite gifts.

Implications of the loss of the creole pig and Haitian rice

It goes without saying that if a dove or rooster cannot be substituted for a chicken, or even a speckled hen for a white one, one cannot substitute an American farm chicken for a Haitian chicken in the service of the Haitian gods. Likewise, the Arkansas rice that has been forced on Haiti by Bill Clinton will not do as a substitute for the three varieties of vastly more delicious Haitian rice in the celebrations of major deities like Papa Legba, or Danmbala and Ayida Wèdo. Similarly, one cannot, in honoring one’s dead, or summoning Bosou or Èzili Dantò, substitute any pig, or even any little black pig, for the creole pig that had been adapted to the island for over 300 years and was eradicated by USAID in 1982. It is important to understand that any blow to Haitian agriculture, any attack on Haitian peasants, is potentially fatal to all Haitian culture and the integrity of Haiti as a nation. Such a blow constitutes no less than a declaration of war on all Haitians, whether they perceive this or not.

I urge every Haitian to consider this: if it takes a lifetime to grasp most religions, you owe it to yourself to study Vodou, for the simple reasons that it is important and an act of self respect, first and foremost, to understand one’s own culture. Some Westerners call Vodou devil worship, but even the more enlightened ones who label Vodou ancestor worship, polytheistic, pagan, animist, or a danced religion, understand it in much the same way that a child thinks it understands a living, breathing animal by saying “cow” when shown a two-dimensional drawing in a picture book. Vodou is all these things, but more than anything, it is the religion of the gods who incited and then fought alongside men in the world’s only successful slave revolt. It is a non-hierarchical, living and evolving religion that cannot be understood by association to known Western concepts. Our ancestors fully deserve to be regarded as deities for having established a new republic, with its culture and language, plus a religion to usher their revolution into a sustainable lifestyle: this, while two-thirds of these former slaves were still transplants from Africa. It is our duty to keep their spirits alive and forever sated and strong.

Sources: For more from Dady Chery, read We Have Dared to be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation, available as a paperback from Amazon and e-book from Kindle and other vendors. | This article is also available in French | Paintings one and nine by Haitian artist and Vodou priest Gerard Fortuné; photograph two by Stefan Krasowski.