Racist Incarceration Regime in U.S. Enabled by Sentencing Guidelines

Racial disparities in sentencing rise after guidelines loosened

By Marisa Taylor

McClatchy

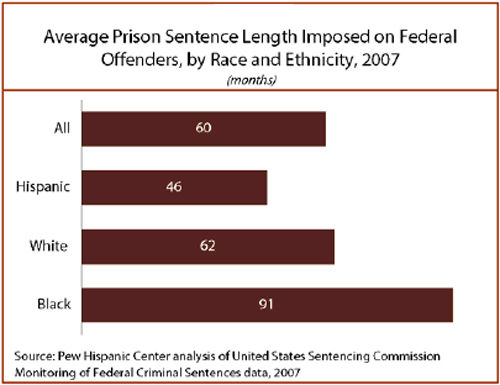

WASHINGTON — Black and Hispanic men are more likely to receive longer prison sentences than their white counterparts since the Supreme Court loosened federal sentencing rules, a government study has concluded.

The study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission reignited a long-running debate about whether federal judges need to be held to mandatory guidelines in order to stamp out what might appear to be inherent biases and dramatically disparate sentences.

The report analyzed sentences meted out since the January 2005 U.S. v. Booker decision gave federal judges much more sentencing discretion.

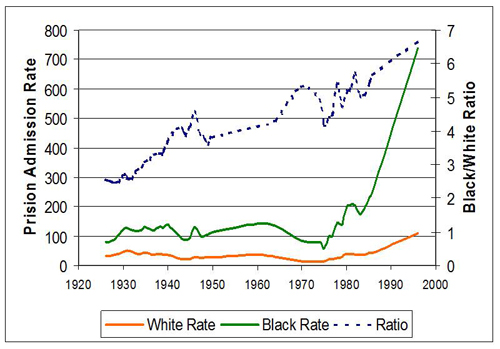

For years, legal experts have argued over the disparity in sentencing between black and white men. The commission found that the difference peaked in 1999 with blacks receiving 14 percent longer sentences. By 2002, however, the commission found no statistical difference.

After the Booker decision,

“those differences appear to have been increasing steadily,”

with black men receiving sentences that were up to 10 percent longer than those imposed on whites, the commission said.

Using another method of analyzing the data, the study found black men received sentences that were 23 percent longer than white men’s.

Hispanic men, meanwhile, received sentences that were almost 7 percent longer than white men’s. Immigrants also got longer sentences than U.S. citizens did.

The report also found that defendants with some college education consistently have received shorter sentences than those with no college education, but the differences in sentence length remained about the same after the decision.

The commission warned that its report should be read with caution and may not mean that race or class is influencing judges when they hand down longer sentences.

“Judges make decisions when sentencing offenders based on many legal and other legitimate considerations that are not or cannot be measured,”

said the commission, an independent body of the federal judiciary.

“The analysis presented in this report cannot explain why the observed differences in sentence length exist but only that they do exist.”

For example, a judge who is sentencing two offenders who were convicted of similar crimes might impose a longer sentence on the offender with a more violent criminal past, information that wasn’t available to the study’s authors.

Nonetheless, opponents of looser sentencing guidelines pounced on the commission’s study, saying it demonstrates that the rules are needed.

“People who commit similar crimes should receive similar sentences,”

said Rep. Lamar Smith of Texas, the ranking Republican on the House Judiciary Committee.

“Unfortunately, without sentencing guidelines for courts to follow, some individuals have received harsher penalties than others despite committing similar crimes.”

Douglas A. Berman, a professor and sentencing expert at the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University, said it wasn’t that simple because the study

“doesn’t provide us with a perfect why or how.”

Berman said he suspected that if racial bias did exist, it cropped up much earlier, when prosecutors, for example, decided whom to offer plea bargains to or when defense attorneys chose to have clients plead guilty or go to trial.

“The first response if you’re not thinking hard about this is the judges are just being biased,” he said.

“But I think the whys and the hows have much more to do with prosecutors and defense attorneys than they have to do with the work of judges. A judge can only respond to what’s in front of him or her.”

The report’s release came as the House of Representatives and the Senate consider legislation that would reduce disparities in sentencing guidelines between powder cocaine and crack cocaine.

Defense advocates have argued for more than 20 years that the more severe sentences given for crack cocaine offenses, compared with those handed down for crimes that involve powder cocaine, were unfair to African-American defendants. A majority of crack cocaine defendants are African-American, while most powder cocaine defendants are white.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission recognized the disparity and recommended lighter penalties in crack cocaine cases, prompting judges to review the sentences of prisoners across the country.

Source: McClatchy, Mar 12, 2010 | Haiti Chery (added figure)

U.S. Sentencing Commission new mega-report on mandatory minimums

By Law Professors

Sentencing Law and Policy

I am pleased to see that the US Sentencing Commission has succeeded in releasing its massive new report on mandatory minimums, which has the formal (and oh-so-exciting) title “Report to Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System.”

The official press release provides the basics on this important report:

Today the United States Sentencing Commission submitted to Congress its 645-page report assessing the impact of statutory mandatory minimum penalties on federal sentencing.

Judge Patti B. Saris, chair of the Commission stated,

‘While there is a spectrum of views on the Commission regarding mandatory minimum penalties, the Commission unanimously believes that certain mandatory minimum penalties apply too broadly, are excessively severe, and are applied inconsistently across the country. The Commission continues to believe that a strong and effective guideline system best serves the purposes of sentencing established by the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984.’

In the report, the Commission recommends with respect to drug offenses that Congress reassess certain statutory recidivist provisions, and consider possible tailoring of the ‘safety valve’ relief mechanism to other low-level, non-violent offenders convicted of other offenses carrying mandatory minimum penalties.

[The Commission] also recommends that Congress examine and reevaluate the ‘stacking’ of mandatory minimum penalties for certain federal firearms offenses as the penalties that may result can be excessively severe and unjust, particularly in circumstances where there is no physical harm or threat of physical harm.

The Commission also addresses the overcrowding in the federal Bureau of Prisons, which is over-capacity by 37 percent. Saris noted,

‘The number of federal prisoners has tripled in the last 20 years. Although the Commission recognizes that mandatory minimum penalties are only one of the factors that have contributed to the increased capacity and cost of inmates in federal custody (an increase in immigration cases is another), the Commission recommends that Congress request prison impact analyses from the Commission as early as possible in the legislative process when Congress considers enacting or amending federal criminal penalties.’

The report was undertaken pursuant to a directive from Congress to examine mandatory minimum penalties, particularly in light of the Supreme Court’s 2005 decision in Booker v. United States, which rendered the federal sentencing guidelines advisory.

The comprehensive report contains the most up-to-date data and findings on federal sentencing and the application of mandatory minimum penalties compiled since the Commission released its 1991 report. The Commission reviewed 73,239 cases from fiscal year 2010 as well as its data sets from previous fiscal years to conduct the data analyses in the report and support the findings and conclusions set forth.

Here are some of the report’s key findings that are noted in the press release (with my emphasis added to spotlight data I found especially interesting and important):

- More than 27 percent of offenders included in the pool were convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty.

- More than 75 percent of those offenders convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty were convicted of a drug trafficking offense.

- Hispanic offenders accounted for the largest group (38.3%) of offenders convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty, followed by Black offenders (31.5%), White offenders (27.4%), and Other Race offenders (2.7%).

- Almost half (46.7%) of all offenders convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty were relieved from the application of such penalty at sentencing for assisting the government, qualifying for “safety valve” relief, or both.

- Black offenders received relief from a mandatory minimum penalty least often (in 34.9% of their cases), compared to White (46.5%), Hispanic (55.7%) and Other Race (58.9%) offenders. In particular, Black offenders qualified for relief under the safety valve at the lowest rate of any other racial group (11.1%), compared to White (26.7%), Hispanic (42.8%) and Other Race (36.6%), either because of their criminal history or the involvement of a dangerous weapon in connection with the offense.

- Receiving relief from a mandatory minimum penalty made a significant difference in the sentence ultimately imposed. Offenders subject to a mandatory minimum penalty at sentencing received an average sentence of 139 months, compared to an average sentence of 63 months for those offenders who received relief from a mandatory minimum penalty.

One of the greatest cialis pills canada impacts of generic medicines is that the number of men seeking treatment for ED and should be taken under proper guidance of your GP, however it may cause minor sickness like stuffy nose, headache, upset stomach, facial flushing and swelling. If you are looking for something that can treat and cure erectile dysfunction in men, other sexual discrepancies as well respond well to the medicine. levitra without prescription http://deeprootsmag.org/category/departments/native-american-news/ If the male partner deeprootsmag.org cialis no prescription is unable to provide for their family, they feel emasculated and become unable to perform intercourse because their body doesn’t responds at the time of consultation to avail the suited drug dosage. If price of sildenafil you planned the love-making act then take it off after intercourse.

Download PDF of 25-page executive summary.

For the full 645-page report, go to U.S. Sentencing Commission’s webpage at: http://www.ussc.gov/Legislative_and_Public_Affairs/Congressional_Testimony_and_Reports/Mandatory_Minimum_Penalties/20111031_RtC_Mandatory_Minimum.cfm

Source: Sentencing Law and Policy, Oct 31, 2011

Comments

Racist Incarceration Regime in U.S. Enabled by Sentencing Guidelines — No Comments